“And unfortunately, in the most recent incidents on two occasions, the actions of People’s Republic of China fighter jets were deemed to be significantly unsafe. As outlined in our Indo-Pacific strategy, we are going to continue to step up our forces in that region,” — Defence Minister Bill Blair regarding the recent confrontations in East Asia.

PART 3

Militarization of Asia and the Pacific?

The year 2018 marked a remarkable yet unheralded shift in Canadian foreign policy in the Asia Pacific. In that year, the Canadian government deployed Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) aircraft and frigates to East Asia in Operation Neon. Additional military commitments followed, and today the CAF is engaged in active deployments around Korea and the South China Sea, frequently leading to confrontations with People’s Republic of China (PRC) forces. Does this new Canadian military profile in East Asia signal a departure from previous Canadian policy and the beginning of a new era of Canadian military intervention in the region? If so, this would constitute a major change that has taken place with little public consultation regarding the potential risks and ramifications.

In this section, we examine the origins of the changes in Canada’s military profile and the correlation with the beginning of a crisis in Canada-China relations in 2018, which subsequently ballooned into Canada’s “China panic.” Tracking the motives, actions, and resistance to the changes that have occurred over the past five years, we provide a provisional interpretation for what has transpired and suggest that the government has aligned the CAF with the US-led military encirclement of China. The significance in this alignment lies in the legitimacy it lends to US operations in the region, and this shift has historical implications because it marks the end of a Canadian policy of avoiding military confrontation in the Pacific since the withdrawal of Canadian troops from Korea in 1957.

The Vancouver Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (January 2018)

In January 2018, Canadian and US foreign ministers, Chrystia Freeland and Rex Tillerson, hosted the Vancouver Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on Security and Stability on the Korean Peninsula. The session brought together representatives of the allied nations that fought in the 1950-1953 Korean War, excluding China, Russia, and North Korea, despite the new peacebuilding initiatives announced by North and South Korea on the Korean Peninsula.

“And unfortunately, what we’ve seen in the most recent incidents, on two occasions, the actions of People’s Republic of China fighter jets were deemed to be significantly unsafe. As outlined in our Indo-Pacific strategy, we’re going to continue to step up our forces in that region.” – Defence minister Bill Blair on recent confrontations in East Asia

Global Affairs Canada stated that the purpose of the jointly sponsored meeting was to “demonstrate solidarity in opposition to North Korea’s dangerous and illegal actions and to work together to strengthen diplomatic efforts toward a secure, prosperous, and denuclearized Korean peninsula. To this end, foreign ministers will discuss ways to increase the effectiveness of the global sanctions regime in support of a rules-based international order.” Freeland stated that “a diplomatic solution” was both essential and possible.

The fact that US defense secretary, Jim Mattis, accompanied Tillerson to the conference, however, underscored the US iron fist in Canada’s velvet glove. Contrary to Freeland’s emphasis on ‘diplomatic solutions,” a Reuters report at the time suggested that the Summit would “probe how to boost maritime security around North Korea and options to interdict ships carrying prohibited goods in violation of sanctions.”

Given its years of deep involvement in the effort to get North Korea to end its nuclear program, the PRC was irate and expressed its irritation publicly: “Since this meeting does not have legitimacy or representativeness, China has opposed the meeting from the very beginning,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Lu Kang stated. “While countries are committed to finding a proper solution for the peaceful settlement of the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue, some parties hold such a meeting in the name of the so-called United Nations command during the Cold War era. We do not know what the purpose of convening such a meeting is.”

After the summit, most commentators professed confusion regarding the goals and outcome of the meeting. One pointed out: “Inexplicably, the event didn’t include global powers Russia or China, North Korea’s most influential neighbors. Instead, countries such as Greece, Belgium, Colombia, and Luxembourg were asked to attend – as if any of them have the clout to help resolve the Korean conflict. The absence of China was particularly perplexing.” A UBC analyst commented that “… our interests in being seen as a middle power in this circumstance are not advanced by being seen as an instrument of a U.S. agenda, advocating a one-note, hard line extreme pressure strategy, and I think particularly in convening meetings in which key players are not involved.”

The confusion and concern expressed in these statements derive from what seemed like a sudden and inexplicable shift from cooperation and engagement with China and Russia to deal with the nuclear issues on the Korean peninsula to one of exclusion and confrontation. The Canadian government soon made clear that it was moving towards further military intervention in the sensitive area, a process that has continued ever since.

Canada’s Military Deploys to the Pacific

The upshot from the Vancouver Summit materialized in April 2018 when Chrystia Freeland announced that Canada would deploy military forces off Korea to enforce sanctions: “Canada has deployed a Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) maritime patrol aircraft in the region to assist in this effort, in addition to assets being provided by the United States and the United Kingdom.” In the four years since this announcement, Canada has extended its military presence in the Asia Pacific. According to the CAF, this escalating presence aims at enforcing sanctions against North Korea, reinforcing partnerships with military allies, or reinforcing “the rules-based international order,” a concept that has been criticized as departing from the centrality of UN principles and international law. Nevertheless, Canada has persisted in a more assertive posture in the Asia Pacific in three distinct areas of operations:

Operation Neon: This new forward military positioning saw Canadian naval vessels, as well as CP-140 Aurora surveillance aircraft based in Okinawa, operating over 1000 kilometers south of Japan beginning in 2018. Over the next five years, nine distinct deployments of frigates have taken place, assisted by supply ship Asterix, and CP-140 Aurora. The CAF has committed to maintaining these operations into 2026. In 2018, Chief of the Defence Staff, General Wayne Eyre, was appointed deputy commander of the United Nations Command in the Republic of Korea, and, according to a 2023 announcement by the Minister of Defence, the next deputy commander will also be a Canadian officer.

News reports indicate that the operations that began in 2018 immediately led to a confrontation with Chinese air forces off the coast of the DPRK. These skirmishes are often referred to as buzzing. As a result, in 2022, the CAF declared that the PLAAF (People’s Liberation Army Air Force) was putting RCAF personnel at risk, an accusation denied by the PRC. Justin Trudeau repeated the complaint in June the following year. Canada’s Operation Neon seems to have exacerbated tensions in the region and deserves critical assessment; however, PRC-Canadian confrontations have not been restricted to Operation Neon.

Operation Projection (Indo-Pacific): In early November (2023), the CBC reported that PRC jets had buzzed a CH-148 Cyclone helicopter operating off the HMCS Ottawa, putting the crews at risk, according to Canada’s Minister of Defence. The frigate and helicopter were operating in the South China Sea. A spokesperson for the PRC Defence Ministry responded, stating that the helicopter had “approached the Chinese airspace in the Xisha Islands recently with unidentified intentions,” refused to respond to warnings, and had taken evasive actions.

What is notable about this particular incident is its location. The skirmish took place not near Korea but in the South China Sea. In 2018, the Canadian government decided to begin conducting “forward naval presence operations in the region as well as conduct cooperative deployments and participate in international naval exercises with partner nations.” These operations aim “to promote peace and stability in support of the rules-based international order.” Operation Projection is distinct from Operation Neon in both its mandate and its area of operations, although overlapping at times.

The first deployment began in April 2018, with the dispatch of the HMCS Vancouver to participate in the US-led “Pacific Partnership 2018,” followed by a series of annual dispatches for military exercises with US forces, often including support for Operation Neon. News reports capture the tenor of these exercises. In September 2023, Canada’s CBC News – The National broadcast a live report from aboard the H.M.C.S Ottawa, a Canadian frigate that was about to join US and Japanese naval vessels to sail through the Taiwan straits, heavily shadowed by PRC maritime forces. The reporter suggested that what was taking place on the water was a “microcosm for deteriorating relations between China and both Canada and the United States.” The news report highlighted this deterioration by recalling that six years earlier, in May 2017, the same warship had arrived in Shanghai to a warm welcome from the PRC’s maritime forces.

In 2021, the Canadian navy participated in a US-led naval exercise, “Pacific Crown,” off Okinawa. Labeled a “stark warning to China,” the war games brought together three Western aircraft carrier strike groups and a Japanese helicopter carrier that’s now able to launch F-35 stealth fighters. The commander of the United Kingdom Carrier Strike Group 21 (CSG21), Steve Moorhouse, told the reporter: “It’s an important message for those here that nations like ourselves do believe in the freedom of navigation, in the freedom of trade and really are alarmed at the militarization of the area…” Western allies can work seamlessly together, he said.

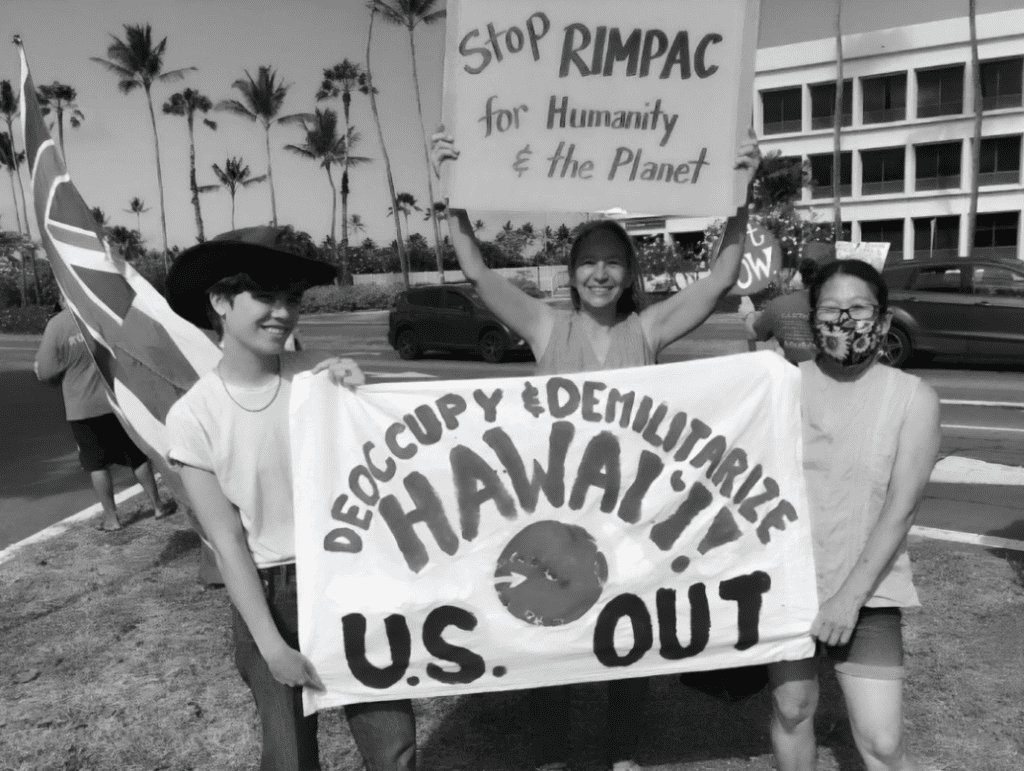

In August 2022, two Canadian warships, HMCS Vancouver and HMCS Winnipeg, departed Esquimalt naval base heading for San Diego and then Hawai’i to participate in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) war maneuvers scheduled from June 29 to August 4. Just as the Canadian warships were departing Esquimalt, activists in Hawai’i gathered at Kailua near the Marine Corps Air Station on Kaneohe Bay to protest the impending visit of the RIMPAC warships, including Canada’s.

The US Pacific Fleet reported that the naval operations ended on August 4: “Twenty-six nations, 38 surface ships, three submarines, nine national land forces, more than 30 unmanned systems, approximately 170 aircraft and over 25,000 personnel participated in the 28th edition of the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC).” The goal was to enhance naval collaboration for the US proposed agenda of “a free and open Indo-Pacific.” For the first time, CAF even dispatched the frigate HMCS Montreal from its Halifax port on the Atlantic to participate in the Pacific war games.

Canada’s Operation Neon, Operation Projection, and its 2022 RIMPAC participation constitute a new military posture in the Pacific for Canada and pose important questions. It has meant that the CAF is now stationing its forces at both the US-controlled Kadena air base, as well as at its naval station, White Beach, on Okinawa, “an island chain doubly colonized by Japan and the United States,” – an island “sacrifice zone,” according to Asian American scholar Jodi Kim. Okinawans voiced their concerns in a recent Global television news report. Has the CAF become complicit in the ongoing dispossession of uchinanchu (Indigenous Okinawans) who, for the past seventy-five years, have continuously fought to regain their lands taken by the US military for military purposes? Is the CAF in contravention of Global Affairs Canada’s commitment to “Enable Indigenous peoples’ representation and meaningful engagement in international discussions and decisions affecting them.”

In addition, the CAF’s view that Operation Neon is a UN-sponsored operation is strongly contested. Certainly, the United Nations has imposed sanctions against the DPRK, but there is no UN mission specifically designated to enforce these sanctions. Operation Neon is instead considered a part of a US-led attempt to utilize the UN Command moniker from the Korean War as a justification for its military enforcement of sanctions. It’s essential to note that this move has never received formal UN approval. The fact that the UN Command has not been formally dissolved serves as a testament only to the ongoing tragedy that both North and South Korea have endured since their annexation by Japan in 1910.

Context and Implications

Peggy Mason, director of the Rideau Institute and former Canadian ambassador on disarmament, pointed out that “we face a daily barrage of material in the media demonizing China at every turn.” Drawing on Jeffrey Sachs, she reminded readers that “the only country with a defense strategy calling for global dominance is the United States of America.” She then highlighted Sachs’ comparison of military deployment: “The US…has around 800 overseas military bases, while China has just one (a small naval base in Djibouti).”

For the most part, however, the deployment of CAF to East Asia has occurred without much discussion or debate in Canada. As the skirmishes with PRC military forces increase, the ramifications are coming home, suggesting that it is worth taking a closer look at the policy shift that has taken place.

Canada’s military capacity in the Pacific remains minor compared to other US allies such as Japan or even Australia. The significance of the recent military deployments and budget increases for the CAF in the Asia Pacific lie elsewhere. A visit to Ottawa by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in August 2019 is suggestive. Canadian Foreign Minister in 2019, Chrystia Freeland, stated in the press conference afterwards that Canada and the US were “indispensable allies” in NORAD and NATO, quickly adding: “Today, alongside our American allies, Canadian armed forces ships and maritime patrol aircraft are deployed under Operation Neon to ensure sanctions are imposed against North Korea, and the deputy commander of the United Nations force in Korea is a Canadian.” Pompeo replied, “I thank them [Trudeau and Freeland] profusely for their solidarity with the United States on a wide range of issues. Chrystia mentioned many of them, but North Korea and Venezuela in particular, Canada has been a fantastic partner.”

Pompeo’s linking Canada’s support regarding North Korea to Canadian support on Venezuela reflects the way in which the US harnesses Canadian actions to justify its own transgressions, which, in the case of Venezuela, was a gross example of both US and Canadian foreign interference in that country. Is this also happening in the Asia Pacific? Is the deployment of the CAF to the Asia Pacific a public commitment on the part of the Canadian government to reinforce the US strategy of military containment of China developed by the Trump administration and continued by the Biden administration?

The US administration that came to power in 2017 unleashed its anti-China hawks (John Bolton, Mike Pompeo, and others) who collectively designated the PRC as its main adversary in the world. As discussed in Part I, both the 2018 National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy focused on China, and the renaming of the Asia Pacific as the “Indo-Pacific” reflected its hopes to recruit India in the encirclement of China. By 2019, the “China Threat” had become dogma, with the Indo-Pacific defined as the military’s “priority theater” according to the US Defense Department’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report.

The hard-line stance against China was then sustained and even intensified by the Biden administration when it came to power in 2021 and announced new measures, including:

- the signing of AUKUS (Australia/UK/US), a trilateral military pact for Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines to deploy against China, a move that caused a furor as it involved Australia tearing up a multi-billion-dollar contract with France.

- Establishing the Quad, a military consultative pact among the U.S., Australia, India, and Japan to encircle China

- creating a new “China Mission Center” within the CIA to address what the agency’s director, William Burns, described as “the most important geopolitical threat we face in the 21st Century: an increasingly adversarial Chinese government,” according to the New York Times.

As a result, what the U.S. today calls its Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) includes approximately “375,000 U.S. military and civilian personnel, including the U.S. Pacific Fleet with approximately 200 ships (including five aircraft carrier strike groups), nearly 1,100 aircraft, and more than 130,000 sailors and civilians. Marine Corps Forces, Pacific comprises two Marine Expeditionary Forces and about 86,000 personnel and 640 aircraft. U.S. Pacific Air Forces include approximately 46,000 airmen and civilians and more than 420 aircraft. U.S. Army Pacific has approximately 106,000 personnel, plus over 300 aircraft and five watercraft, along with more than 1,200 Special Operations personnel. Department of Defense civilian employees in the Indo-Pacific Command AOR number about 38,000.” This level of lethality represents an ongoing threat to peace in the Pacific.

Canada’s defense establishment anticipated and then fully embraced augmenting the US military presence in the Pacific. By October 2022, Canada’s Chief of Defence Staff, Wayne Eyre, declared, “Russia and China are not just looking at regime survival but regime expansion. They consider themselves to be at war with the West,” he said. “They strive to destroy the social cohesion of liberal democracies and the credibility of our own institutions to ensure our model of government is seen as a failure.”

The CAF’s military tilt toward the Pacific was reinforced in Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy released in late 2022. “We are not just going to engage the Indo-Pacific; we are going to lead,” stated Canada’s Foreign Minister in announcing the new strategy. China is identified as an “increasingly disruptive global power that Canada would challenge whenever necessary” and only cooperate with “if we must.” It allocated nearly $500 million to increase the Canadian military’s presence in the Asia Pacific and more than $227 million to bolster its national security agencies (including CSIS, CSE, RCMP, and CBSA) in the region. This funding reflects an expanded role for the Five Eyes intelligence network in Asia and the Pacific.

Historicizing the Shift

When we historicize Canada’s recent military tilt into the Pacific, it suggests that what we are witnessing is, in fact, a departure from previous Canadian military policy in Asia and the Pacific.

The CAF participated in the Korean War from 1950-1953; however, the 1953 armistice in Korea followed by the 1954 Geneva accords led to the withdrawal of all Canadian troops from Korea by 1957. In 1955, when the U.S. government promoted the idea of a NATO-type alliance for Asia, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), “Canadian reaction was negative,” and it declined to participate. Since then, the Canadian government has avoided military deployments to Asia, except for minimal participation with its allies or as part of peacekeeping missions, such as the International Commissions for Supervision and Control (ICSC) for Indochina (1954-1974).

Canada’s participation in the ICSC was one of the starting points for Canada’s reputation as a peacekeeper, allowing it to refrain from sending troops alongside the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand contingents fighting in Vietnam. Ironically, it was the People’s Republic of China, along with India, that nominated Canada to the commission in 1954.

For Lester Pearson and others, the ostensible and practical reason to avoid participation in SEATO or deploying military forces to Asia and the Pacific was that they saw the deployment of armed forces to Asia as possibly detracting from Canada’s military commitment to NATO. There was an additional reason, however. Pearson and others, including John Holmes, who the RCMP hounded out of Canada’s foreign affairs department because he was gay, had begun to see the need for a degree of Canadian autonomy as a counterweight to its dependence on the United States. This gave rise to theories of Canada as a “middle power,” which meant that Canada could “when we want, differ from our major allies and do not belong to any bloc.” The advent of Pierre Trudeau to the leadership of the Liberal government in 1968 saw further shifts, including, finally, recognition of the PRC and a more active but peaceful foreign policy for Canada in Asia and the Pacific. Some scholars and officials in Canadian foreign policy communities continue to aspire to this notion, while others promote closer integration with the U.S. empire.

Canada’s new military profile in the Asia Pacific is a definite step towards tighter military integration with the U.S. in Asia and the Pacific, a de facto reversal of a policy to resist military intervention represented by Canada’s refusal to join in SEATO. Additionally, aligning the CAF with the U.S. military in the Pacific suggests that Canada’s aspirations as a ‘middle power’ hold little relevance today. Instead, the Canadian government is again taking its lead from the Five Eyes.

Canada, the Five Eyes, and the Pacific

The states in the Five Eyes—the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—constituted a historically powerful bloc in Asia and the Pacific, often allying with others, including Japan, South Korea, and some Southeast Asian nations to assure US power in the Pacific. Understanding the genealogy of this bloc reveals insights into the politics of race and empire in the region.

The Five Eyes alliance came together in the 1948-52 period initially as an intelligence-sharing arrangement. It evolved out of Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain racializing appeal at Fulton, Missouri, in 1946, where he called for a “fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples” to enforce world peace. Aimed at the rising forces of decolonization, Churchill’s speech was a paternalistic call to arms: “This means a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States… If the population of the English-speaking Commonwealth be added to that of the United States, with all that such cooperation implies in the air, on the sea, all over the globe, and in science and industry, and in moral force, there will be no quivering, precarious balance of power to offer its temptation to ambition or adventure.”

Appealing for unity of the Anglosphere, Churchill was, in fact, calling for the strengthening of a US-UK-centered alliance to perpetuate liberal imperial power and to assure the continuation of global white supremacy. One of the outcomes of this appeal was the creation of the Five Eyes alliance (among the English-speaking states), which was to become both a political and intelligence bloc. Its racial origins still echo today in the comment by retired Canadian Brigadier-General James Cox that the Five Eyes have an “affinity strengthened by their common Anglo-Saxon culture.”

In the immediate aftermath of the Pacific War, the Five Eyes alliance was instrumental in constructing what Japanese American historian Akira Iriye described as the “San Francisco System.” Named after the city that hosted the signing of the peace treaty with Japan in 1951, Iriye described what emerged between 1945 and 1954: “The rearmament of Japan, continued presence of American forces in Japan, their military alliance, and the retention by the United States of Okinawa and the Bonin Islands. In return, the United States would remove all restrictions on Japan’s economic affairs and renounce the right to demand reparations and war indemnities. Here was a program for turning Japan from a conquered and occupied country into a military ally…”. The U.S. also supported military alliances between New Zealand and Australia and signed pacts with the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as Japan.

The US was able to mobilize the Five Eyes bloc to support its intervention in Korea and to assure its domination of the peace treaty conference in San Francisco, which was effectively a peace treaty without Asia. Most countries that had suffered from Japanese imperialism were either excluded or boycotted the conference or refused to ratify the treaty. Many of the territorial disputes in East Asia currently in the news date from this unjust treaty. The Five Eyes, however, provided the legitimacy for the war in Korea, the peace treaty, and the San Francisco system that emerged at the time. While most commentators frame this as part of the “Cold War” with the Soviet Union (and later China), applied to Asia, the term is entirely Eurocentric and misleading.

Assured of support among its Five Eyes allies, US hegemony in the Pacific was predicated on stopping decolonization and blocking national liberation movements in Indochina, Indonesia, Malaysia, China, Burma, and elsewhere unless they adhered to US control. Those who pursued an independent course were subsequently considered offshoots of Soviet expansionism, a reductionist absurdity rife with racist overtones. The results were the Korean War and Vietnam wars, with their horrendous loss of life.

Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Labor Center and founding director of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, points out that, historically, anti-Asian violence in the United States is directly related to US foreign policy in Asia: During the Vietnam War, Asian people were dehumanized. The brutal massacre of Vietnamese women and children in My Lai, Vietnam, was conducted by U.S. soldiers who viewed the Vietnamese people as less than human. The U.S. military used napalm, Agent Orange, antipersonnel weapons, and massive bombings to target and kill millions of civilians, all justified through the lens of white supremacy and anti-communism.

Today, that violence has re-emerged as successive US administrations brandish an inflated “China Threat,” seeking out eternal enemies to justify their global wars. This rebranding of the ‘Yellow Peril” reflects the persistence and malleability of racist perceptions of Asia. These warnings echo those by Yuen Pau Woo, Xiaobei Chen, and others cited earlier in this paper.

Unfortunately, the recasting of the Canadian presence in Asia as a military one, in the midst of Canada’s “China Panic,” returns us to an era rife with the dangers of racism, anti-communism, and war. Given this context, Canada’s justification for its intervention—that it is conducting UN operations near Korea or enforcing the “rules-based international order”—deserves much closer scrutiny.

Australian historians Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds point out in “Drawing the Global Colour Line” that the US-UK-Australia invasion of Iraq in 2003 “recapitulates the Anglo-Saxon solidarity of earlier times with devastating consequences.” Is Canada now in the process of doing in Asia what we wisely avoided doing in Iraq in 2003? Ongoing pressures to conform to the demands of the US empire in the Pacific derive to some extent from the similarities between Canada and the United States as settler colonies. Of the Five Eyes, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are settler offshoots from their progenitor, the United Kingdom. The westward expansion across the Pacific was predicated, first and foremost, on the dispossession of Indigenous peoples in these settler colonies. Subsequent expansion across the Pacific and into Asia forced an accommodation between the imperial powers, the UK, and the US.

The smaller settler states of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have not always adhered to the policies of the UK-US axis. However, Canada’s “China Panic” today, with its ongoing deployment of Canadian forces to East Asia, suggests that the era of Canada searching for autonomy from the US is no longer on the agenda, particularly given the NDP’s hostility towards China. Are we now witnessing Canada’s evolution into a ‘sentinel state’ for the United States?

In an increasingly polarized world, millions in the streets of both the global north and south are aligning themselves against the forces of what some call colonial racial capitalism. Those of us on the territories called Canada are increasingly obliged to begin difficult conversations and make critical decisions as we face the existential crises of war and environmental degradation that imperil planetary survival. May we do so in a way that unifies the many and isolates the forces of empire and war.

Contributors

John Price is a historian with a focus on Asia and the Pacific, as well as Asian Canadian history. An emeritus professor at the University of Victoria, he is the author of “Orienting Canada: Race, Empire, and the Transpacific” and, with Ningping Yu, “A Woman in Between: Searching for Dr. Victoria Chung.” As an anti-racist educator, he has worked extensively with racialized communities, co-authoring “Challenging Racist British Columbia: 150 Years and Counting” and “1923: Challenging Racisms Past and Present.” John Price has written extensively for publications such as The Tyee, the Victoria Times Colonist, Georgia Straight, the Hill Times, Canadian Dimension, and Rabble.ca. He is a board member of Canada-China Focus and a member of the National Security Reference Group of the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT).

The National Security Reference Group (CAUT): The Canadian Association of University Teachers established this group in the spring of 2023 in light of growing concerns about racial profiling and restrictions to academic freedom arising from new national security guidelines being imposed by the government on researchers. Composed of representatives from universities across the country, the reference group monitors the impact of such guidelines and advises the Canadian Association of University Teachers on potential measures to counteract the effects of racial profiling and restrictions on academic freedom. Members of the group contributed to this discussion paper through their ongoing efforts and critical analysis, providing specific materials for the paper, and offering feedback on initial drafts.

Acknowledgments

This discussion paper could not have been written or published without significant contributions from many people. The Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives at the University of Victoria generously stepped forward and agreed to publish the paper despite the risks associated with the current anti-China atmosphere. Special thanks to Helen Lansdowne (associate director), Victor V. Ramraj (director), and Katie Dey (office manager and communications).

Much appreciation to those who took the time to review and comment on the manuscript, including Paul Evans, Gregory Chin, Midori Ogasawara, and individual members of CAUT’s National Security Reference Group. Senator Yuen Pau Woo has provided support in multiple ways despite trying circumstances. Many thanks to Patricia Kidd for the meticulous copy editing, and to John Endo Greenaway for the stellar design and layout.

Finally, my thanks to the board, staff, and supporters of Canada-China Focus, who have been both inspiring and instrumental in bringing this project to completion.

- The paper was first published by the CAPI Working Paper Series.

Disclaimer:

Voices & Bridges publishes opinions like this from the community to encourage constructive discussion and debate on important issues. Views represented in the articles are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the V&B.