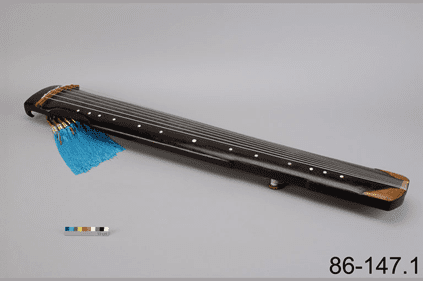

Guqin, part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity, was made using Canadian fine red pine for the Long Yin. This demonstrates Canada’s success in promoting multiculturalism. The instrument produces a fine tone and is worthy of preservation.

By Ban Zhang

Thirty-nine years ago, Zheng-hua Zheng (郑正华) received a mail from Canada Post at his basement domicile on Vancouver’s east side. It was a letter-sized yellow envelope bearing the National Museums of Canada logo printed in the top-left corner. Upon opening the envelope, Zheng found a handwritten letter informing him that his handmade ‘Chinese Zither’, more accurately known as a Chinese Guqin, had been accepted as a permanent addition to the department’s collection.

An online picture of Zheng’s Guqin collected by the Canadian Museum of History, showing Place of Origin: Country - Canada, Province - British Columbia (Résultats de la recherche / Search Results (historymuseum.ca)

Zheng was gratified to receive this acceptance letter from the National Museums of Canada, which exemplified recognition of his made-in-China talent and his borderless artistic contribution to this welcoming country. Zheng’s Guqin stands today as a testament to a newcomer’s long and lonely journey from surviving to thriving.

A Childhood with Museum Immersion

Zheng was born in Shanghai to a well-known family that was originally from Ningbo, a city located 200 miles south of Shanghai. His family had many scholars who turned into officials for generations during the Qing Dynasty. The highest-ranking official in his family was the second-grade official, an equivalent to the Deputy Prime Minister these days.

One of the notable family stories is about his ancestral home, which was famous for its library building known as the ‘Erlao Pavilion’ (二老阁). The family had a vast collection of classic books, many of which were later donated to a state-run museum for better preservation and maintenance.

Zheng was not aware of many stories and family histories until he reached adulthood. However, what stands out the most from his childhood are the frequent visits to various museums and art exhibitions. Zheng explained that the reason for such visits was quite amusing – “We are a family of six children, and my mother thinks that the six children together are too noisy and busy at home, so my father often takes some of us out.”

Zheng’s father was a cloth designer, no fashion designer then in China. He took advantage of this babysitting time to explore local museums and exhibitions to gain insight into the dynamics and trends of art for his work. During these visits, Zheng was most impressed by various shapes and styles of Chinese traditional musical instruments, including Guzheng (古筝) – a Chinese zither, Erhu (二胡) – the Chinese violin, Dizi (笛子) – a Chinese transverse flute, Pipa (琵琶) – the Chinese guitar, Guqin (古琴) – Chinese seven-string instrument, to Xiao (箫) – a Chinese vertical end-blown flute and many more.

This immersive museum experience inspired his career path and deepened his connection to museums.

A Gifted Student Follows Masters

During his Grade 4 in elementary school, a senior student who volunteered to teach younger classmates introduced Zheng to the musical instrument Dizi. With only twenty cents to spend from his pocket money, Zheng purchased his own Dizi and began playing. This marked the start of Zheng’s career as a musician.

Zheng feels fortunate that he was able to learn music from his masters. He first learned basic fingering from a senior student, but became obsessed with the flute and practiced wherever and whenever possible. A few years later, the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra established a music school and recruited 20 students. Zheng was qualified to study Dizi professionally under the apprenticeship of Chunling Lu (陆春龄), a master Dizi soloist known as the “Chinese Magic Dizi”. At the time, Zheng was fourteen years old.

When Zheng was a teenager, he showed exceptional talent in playing the Dizi. Yude Sun (孙裕德), who was then the deputy head of the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra, recognized his talent and accepted him as an apprentice. Sun, who was known as the “King of Xiao”, taught Zheng how to play Xiao and Guqin duets in rich, subtle, and elegant sounds, which highlighted the profound meaning of Chinese classical polyphonic music. Zheng was sixteen.

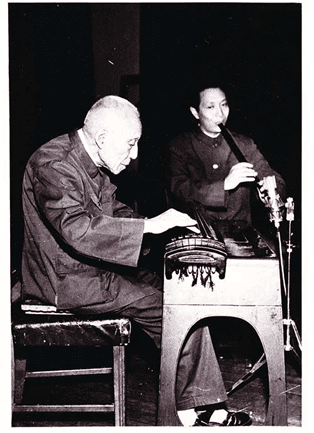

Zheng’s third apprenticeship ceremony officially took place when he turned thirty. However, he had already been learning Guqin from Ziqian Zhang (张子谦), who was a master of Guqin and had been playing Guqin and Xiao duet repertoires with Sun in the Orchestra for decades. Over time, Zhang and Zheng developed a friendship that went beyond the typical master-and-apprentice relationship, becoming colleagues and friends.

Zheng and his master Zhang performed Guqin and Xiao in duet, 《梅花三弄》(‘Three Variations of Plums Blossom’) at ‘Spring of Shanghai Music Festival’ in 1979 (Photo provided by Zheng)

When the Cultural Revolution erupted, every day was a day of anxiety and fretfulness for everyone in the Orchestra. Zheng and Zhang supported each other through difficult times, protecting their careers, their lives, and the precious Guqin pieces that were as important as their lives.

Zheng followed the teachings of several masters and became a proficient player of Dizi, Xiao, and Guqin, both solo and in duets. He also acquired the skills to repair old Guqin and even make new ones from scratch. By the time he was thirty years old, he had become a well-known musician with a diverse set of talents, just as Master Confucius (孔夫子) had envisioned.

A Blade of Grass on the Kunlun Mountains

Turning to the 1980s, China’s Cultural Revolution had finally come to an end and the country had opened its doors to the world. Zheng was among the first wave of Chinese citizens longing for a jump-start and panting for a deep breath. With a hard-to-obtain family visitor’s visa and just $200 in his pocket, he arrived in Vancouver alone. Unfortunately, his relative had left for Hong Kong, leaving Zheng to fend for himself. Although he was already 35 years old, he was determined to make a fresh start and build a new life from scratch.

Zheng often refers to himself as ‘A Blade of Grass on The Kunlun Mountains.’ This is the title of a 1962 Chinese drama film that tells the story of a young girl who goes to work at Kunlun Mountain after graduating from school. The girl decides to overcome all the difficulties she faces with the help of a passionate and determined woman. Located in Western China, the Kunlun Mountains are known as the ‘Forefather of Mountains’ in China.

Before coming to Canada, Zheng had read about the Vancouver Chinese Orchestra in the news. He decided to reach out to the head of the Orchestra and found out that all its members were part-time music enthusiasts. The Orchestra was in search of a professional who could help them with their practice and performances.

It appeared to be an ideal fit. After coming to Canada, Zheng offered his services as a volunteer to the Orchestra based in Chinatown. He helped with arranging, conducting, and guiding rehearsals to the best of his ability for nearly three years while waiting for his immigration application to be processed. During this period, Zheng was invited to perform a solo concert at the University of British Columbia, where he showcased his talents as a well-known professional Guqin player.

Over time, many audiences in Vancouver developed an appreciation for the Chinese Guqin, an instrument that produces subtle and refined sounds. Some even asked Zheng to teach them how to play it. Zheng didn’t shy away from admitting his financial struggles during his early days in Canada. He had to walk two hours from West Vancouver to Chinatown to give lectures to save money on transit tickets. As he was on a visitor’s visa, he was not allowed to work until he received his permanent resident status.

After a long wait, Zheng finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel. He qualified for the special talent category and with strong material and moral support from the Vancouver Chinese community, his immigration application was approved two years later. At the age of thirty-seven, he was finally able to start a new chapter in his life.

A Chinese Guqin Made in British Columbia and Collected by Ottawa

When teaching Guqin, Zheng’s students needed an instrument to practice, but local stores had none. So, he began making Guqin for his students.

The Guqin is one of the oldest plucked instruments in China, similar to the Guzheng or Chinese zither. It is also known as the Qixianqin (七弦琴) or ‘seven-stringed zither’ due to its seven strings. The main part of the Guqin is a long and narrow wooden soundbox. A well-crafted Guqin can imitate the sounds of nature, including wind blowing, rain falling, rivers gurgling, and dell-echoing.

It is said that when teaching his students, Confucius was known to play the Guqin – an instrument representative of traditional Chinese musical culture.

The secret lies in the tonewood, but where could such a tonewood possibly be found in Vancouver? One day, Zheng walked alone along BC’s Sunshine Coast beach, feeling homesick for his family on the other side of the Pacific. Suddenly, he noticed that the rising tide had washed a piece of driftwood ashore. Seeing this, he sighed, feeling like he was just like a piece of driftwood that had come a long way to BC. He asked himself whether this piece of wood could be put to better use or whether it should just be left lying on the beach forever.

Zheng picked up a small dry piece of driftwood and tapped it using his index finger joint, creating a soft ‘Bang, Bang, Bang.’ Zheng knocked on wood.

Red pine wood found in Canada is known for being soft and having a straight grain, which makes it an excellent choice for making a Guqin. Driftwood that has been exposed to natural elements such as wind, rain, sun, and seawater for many years is ideal for creating a perfect tonewood for Guqin.

To improve his teaching, he attempted to make a few pieces of Guqin. In 1983, he created a pair of Guqin instruments, each carved with two Chinese characters, Long Yin (龙吟), literally ‘the dragon roar’. This was intended to symbolize the sounds of great subtlety and refinement. One of the two pieces was subsequently chosen for permanent collection by the National Museums of Canada in 1985, while the other piece was used for his performance.

Also in 1985, his wife and daughter reunited with him in Vancouver and their family was finally whole again, like strings attached to a soundbox.

Zheng is making a Guqin using BC pine wood in his backyard (Photo provided by Zheng)

An Ambassador Promoting Harmony with Melody

Before arriving in Canada, Zheng had performed on the bamboo flute for various Heads of State across the world, including France, Spain, the United States of America, Yugoslavia, Denmark, Canada, and other countries. Additionally, he had taken part in numerous significant music festivals. As a result, Zheng had already gained recognition both within China and internationally.

After his debut solo concert at UBC, Zheng received invitations to perform both locally and internationally.

In 1985, he performed a flute solo at the Vancouver Folk Festival. During the performance, he played various types of flutes and traditional Chinese wind instruments. According to the festival’s website, the word ‘play’ doesn’t accurately describe his performance. He managed to make the instrument sing, dance, laugh, cry, jump up and down, turn somersaults, and even spit wooden nickels.

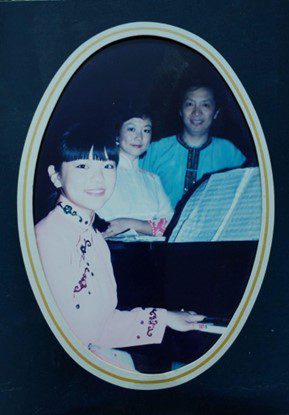

The next year, Zheng’s family was invited to perform at the 1986 World Expo Vancouver. His wife, who was a master of Guzheng, and his 13-year-old daughter, who was a gifted piano student, joined him in duets. The family gave 100 performances in just one month. To acknowledge their unique contribution to the Expo, then BC Premier William N. Vander Zalm issued a Certificate of Award of Merit to Zheng and his family.

Zheng’s family performed at the 1986 World Expo Vancouver (Photo provided by Zheng)

The family received invitations to perform in various parts of Canada. On March 20, 1986, the Manitoban News published an article titled ‘Magical Music of China’. The article stated that Zheng’s concert of traditional Chinese music validated the soundness division proposed by Curt Sachs. According to Sachs, the harmony of the Western classical world, the rhythm of Africa and South America, and the melody of the Eastern countries were distinct and separate.

Zheng has an impressive list of international performance tours. This includes performances at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1987, the Taipei National Concert Hall in 1988, Kaohsiung Taiwan in 1990, the Indiana National Museum in 2005, Changhua Taiwan in 2011, and Confucius Temple in Ningbo in 2023 among many others.

Zheng’s passion for music and his desire to spread harmony is evident wherever he goes. His dedication to playing the Guqin and using its melody as a tool for promoting calm and peace is truly inspiring. Zheng’s efforts to bridge cultural differences through the universal language of music is a shining example of how we can all work together to create a better world.

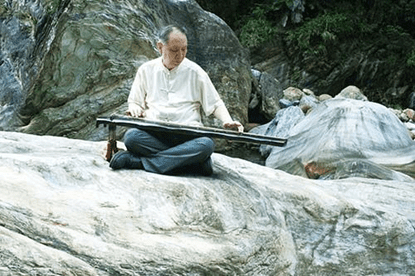

A Teacher with Students All Over the World

The Guqin is often played with two famous melodies called Gao Shan《高山》 (‘High Mountains’) and Liu Shui《流水》 (‘Flowing Water’). These two pieces were originally played by a renowned Chinese musician named Bo Ya (伯牙) who lived during the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history, which lasted from approximately 770 to 481 BC. Bo Ya had a close friend named Zhong Ziqi (钟子期) who understood his music completely. After Zhong Ziqi passed away, Bo Ya broke his Guqin because he believed that nobody else in the world would understand his music. Therefore, these melodies have come to symbolize the idea of true friendship in Chinese culture. In Chinese, the term Zhiyin (知音), which literally means ‘to know the tone’, refers to a close friend who truly understands you.

In 2017, he played ‘High Mountains and Flowing Waters’ in Taroko National Park, Taiwan (Photo provided by Zheng)

As the Chinese proverb goes, it is easier to earn a lot of money than to find a true friend (‘千金易得,知音难求’). Zheng has his secret to this, “Instead of searching for a true Zhiyin, I teach them to play Guqin so that they can become one.”

Now in his late seventies, Zheng’s focus has shifted towards teaching the younger generation, rather than performing himself. He remembers vividly how his masters Lu, Sun, and Zhang had turned him into a professional musician.

He also happily recalls how his former students became leaders in various fields. He has been a guest lecturer of folk music at UBC for three years since 1985, a visiting professor at the National Taiwan University of Arts for three years since 1988, a Guqin teacher at the Daohe School in Taiwan for three years since 1990, a speech tutor for the general education course ‘Art and Life’ at National Chung Hsing University in Taiwan in 2004, and a visiting professor at the Nanhua University in Taiwan in 2012. His students are spread all over the world.

These days, Zheng’s students of all ages are fans of traditional Chinese music, especially the Guqin melody. Zheng hopes that one day, his Guqin melody will attract more fans and they will become close friends.

A Guqin Legacy Worthy of A Museum Collection

If true friendship is worth more than gold, Zheng’s handmade Guqin could be worth a museum collection. The Long Yin Guqin, which was made in British Columbia, was added to the Canadian Museum of History’s collection in 1985, demonstrating its historical significance.

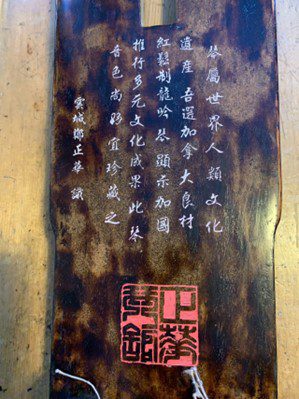

Zheng, a skilled musician, created a second Guqin instrument besides the one displayed in the museum. He has been performing with this instrument for many years. The art of playing Guqin was recognized as a UNESCO ‘Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’ in 2003. To commemorate this achievement, Zheng hired a calligrapher to carve a message on the back of his Long Yin Guqin.

Guqin, part of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity, was made using Canadian fine red pine for the Long Yin. This demonstrates Canada’s success in promoting multiculturalism. The instrument produces a fine tone and is worthy of preservation.

Calligraphy carved at the back of Long Yin Guqin (Photo provided by Zheng)

As someone who grew up immersed in museums, Zheng understands the big impact that a small item in a museum’s collection can have on younger generations.

- Ban Zhang is a Vancouver freelance writer.

Disclaimer:

Voices & Bridges publishes opinions like this from the community to encourage constructive discussion and debate on important issues. Views represented in the articles are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the V&B.